Trauma in the Body

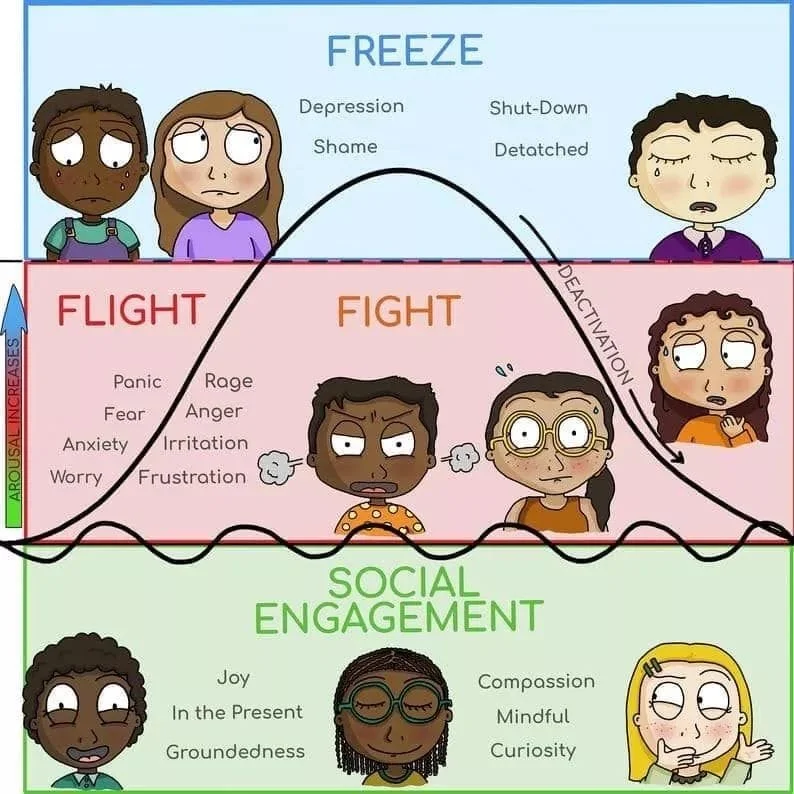

The image I used does a pretty good job of representing how we tend to move through stress responses. The squiggly line with the short waves shows how a person might experience ‘normal’ stress responses in a typical day. Small* things can set this off - like a person being disrespectful to you or nearly getting in a car accident while driving to the grocery store. These types of experiences can send us into the Flight or Flight Zone but not so badly that we need time to regulate again after. We might notice an increase in heart rate, but it levels out again in a reasonable amount of time. We are typically in and out of these ‘smaller’ stress responses in a day.

The larger single wave shows that there is a positive correlation between the intensity of the state of arousal and the time it takes to recover homeostasis (the home base or base line of being). When we are faced with a threat or notice we are in an overwhelming situation, our body and brain signal to the amygdala that we need to go into Protect and Survive Mode. The idea is that we need to conserve body resources to have the best chance at escaping the threat at hand.

So, the amygdala signals to the heart to increase its beats per minute so that it can stimulate blood flow throughout the body – we might need to run away or fight. It tells the endocrine system to release adrenaline in case of flight and cortisol to signal other parts of the brain and body to back off – we might need to make quick decisions to get out of the situation, there might not be time to deliberate or compare against past experiences. Sometimes this means that we aren’t as readily able to access the rational, decision-making part of the brain (the prefrontal cortex). Our senses seem to heighten in these situations as well – the higher functioning systems of our brain and body are essentially put on hold so that the baser functions can thrive in the name of keeping us safe and alive.

Once we know that the threat is no longer in front of us, the amygdala signals the same systems to come back to normal and allows the higher functions to resume. The heart rate decreases, blood flow calms, and thoughts slow down and become more rational. The amount of time this takes depends on many things. For example, for someone who has never seen a bear in the woods before, they would have a more severe reaction than a hunter would. Another factor is the threat itself. I know when I am in a situation where I’m nearly struck by another vehicle it spikes my heart rate and sends a rush of adrenaline through my body, but five minutes later I’m back to baseline. However, having been in a car accident, those responses take much longer to resolve. In the case of a bad collision that I was in as a driver, it took me until that evening when I was back at home before my functions started to resume as normal.

So much of how our brains and bodies respond to our environment has to do with the primal instinct to keep us safe and alive. When we talk about someone having experienced trauma we are typically referring to instances of that single-wave, intense response. Often (but not always) in the case of more overt trauma those are repeated experiences, meaning a person is recovering from intense states of overwhelm more than once or over and over again. When we look at the context of survival response in terms of trauma it becomes evident that over time we have developed this evolutionary survival response that is intense but effective. One of the problems we face is that we aren’t necessarily adept at processing those experiences after they occur. Once our rational brain resumes its functioning, we should be taking space to go over the situation and process what we experienced.

Notice how the single wave in the graphic doesn’t actually dip back down to the Social Engagement Zone. That’s because in order to truly reconnect to that zone a person must confront and deal with the event that caused that big arousal. Once we are safe, we need to go through what happened and acknowledge our response (whether good or bad) and know that we were limited in those moments during the heightened state of arousal for a good reason. We need to accept what happened and reinforce our belief that our brain and body knows how to keep us safe. There may even be other layers that factor in, like if the trauma was caused by another person there may need to be a healing of the harm that was done (whether intentional or not). Sometimes we don’t have the option to heal with that other person, but the healing still has to occur. Our bodies can re-establish our vital signs enough and maybe our brains can help us ‘try to forget’ what happened, but that isn’t actually dealing with, rationalizing, or healing the experience.

When our brains signal to our body to respond to a threat or a threatening situation, and then we re-establish the baseline, the journey doesn’t end there. It becomes an information-packed memory to serve as survival knowledge in case we have to experience the threat again. When we process the event properly that memory can be stored with the information but with a different code for emotion. When we store that memory without processing properly first, we risk a slew of emotions that don’t necessarily belong with that memory. For example, if I were to get into a conflict with a friend and I was feeling attacked and defensive my body would respond accordingly (in my case, I would be up in the higher part of the flight/fight zone). If we walk away from each other to calm down but don’t come back and talk about it later to resolve the issue, then that memory is stored with judgment, resentment, anger, and maybe some sadness for feeling hurt.

Now, if my friend and I talk about it after and we resolve our feelings about it, I may still feel a little resentful or sad, but the emotion code is different. Next time I find myself in a conflict with this (or another) friend, my memory of that experience will guide my reaction. If the emotions stored with that memory are intense then I’m probably going to respond intensely to the next conflict. If I healed from that initial conflict, then I’m likely to handle the next one better. Or better yet, avoid it all together because I’ve learned what initiated that first argument and now I know better how to communicate with that person.

Often, we store negative experiences and traumas away – far away. We have language around ‘repressing’ our emotions. I have been guilty of this almost my entire life. The awesome thing is that I’m learning about my behaviours and the importance of pivoting my habits and reactions. The problem with repressing or pushing our memories down, or living as though it never happened, is that it still exists in our body. Just because we are ignoring it doesn’t mean it goes away. And without the knowledge and wisdom that’s contained in those memories, we are ultimately limited in our infinite potential. Even take the case of a fight with a friend – it’s something kind of normal, it’s common, many people can relate and experience this regularly – how we process those experiences has a profound effect on how we deal with things in the future. When we consider experiences that are more intense and impactful than those more ‘normal’ occurrences, it is even more crucial that we process them properly. We deserve all the wisdom our bodies have to offer us. It no longer makes sense for me to ignore the unhealed parts of me because I can see that it’s just keeping me from being me. Trauma goes so much deeper than the brain and body. While it can be scary to thinking about healing ourselves, we must remember what’s on the other side of the healing. Because it is beautiful and amazing, and we deserve that.

*to qualify the size of a problem - what is small to me might be big for you. In these discussions there are always many facets and variables that make them ultimately subjective situations.